Achaemenians in Sindh (516-400 B.C.)

Before Independence, the Achaemenian conquest and rule of Sindh was known from Herodotus[1] as well as Persepolis Naqsh-i-Rustams inscriptions[2]. The Voyage of Skylax from Peshawar via the Indus to the Red Sea to connect Sindh and Egypt, the two granaries of his empire at orders of Darius-I also comes from Herodotus. Olmstead[3], is the first authority on Achaemenians, who has gone into details of their provincial administration, taxation and benevolent rule after independence. He thinks they were not despots but rather kings of Council. Under them the Provincial Governments had autonomy and they were the first to connect the remote provincial cities to each other and the Imperial capital. They were also the first to provide world currency against local coinage. They were also the first to provide world currency against local coinage. They adopted Aramaic (northern Mesopotamian language) as official language and not Avasti (the Ancient Persian). Ghirshman is another authority on the subject. Basing on Herodotus and Hecatus, he describes Darius-I’s successor Xerexe’s war with Greeks, in which the meds of Sindh and the Punjab under Persian generals took part[4]. Lambrick too had briefly described Achaemenian rule of Sindh, Sindh became independent of Achaemenian rule some where between 450-400 B.C. In the latter year Egypt too became independent.

Alexander in Sindh (325-324 B.C.)

For nearly 250 years European colonizers of Asia, took keen interest in Alexander and his exploits. His historians run into many hundreds. Prof. Robin Fox-Lane[5] in Alexander the Great has used more than 1370 sources written in past 200 years. Although each one of his original historians i.e. Ptolem Soter, Aristobolus, Clitarchus, Justin, Arian, Diodorus, Strabo, and Plutarch[6] had mentioned Alexander’s military operations in Sindh and translations were available, no attempt was ever made to write detailed history of Alexander in Sindh. The first such attempt has been done by Lambrick in History of Sindh, Vol-II, with a map on Alexander’s route and courses of the Indus in Sindh around 325 B.C. Holmes and Wilhelmy[7] in their maps have increased our knowledge of historical-geography of the period. Eggermont[8] is the only another, who has written a complete volume on Alexander in Sindh and Balouchistan, though the learned professor had done a few basic blunders in his investigations. In presence of all these new sources, it is a ripe time, to write on Alexander’s operations in Sindh. M. H. Panhwar’s Chronological Dictionary of Sindh’ has a map of Alexander’s conquest and retreat based on these new and old sources.

Mauryans in Sindh (324-187 B.C.)

Smith[9] and Rapson[10] were the best sources on Mauryans, before Independence. No work of note has been done on Mauryans since Independence. Mookerjee[11] is the only authority who had done some additional work on Mauryans. Even this work is more than 30 years old. Mookerjee thinks that Chandragupta started the War of Independence in 323 B.C. There is a thinking that Moeris-I and II rulers of the Lower Sindh (Patalene) were Muryans related to Chandragupta and it was with their help that anti-Greek movement started in Sindh, while Alexander was still at Patala. Based on above 3 sources and also Eggermont[12], it is possible to reconstruct Mauryan rule in Sindh. Lambrick’s work is based on Smith and Rapson[13], but routes in Sindh. Are his own which have been copied by Robin Fox lane in on Alexander’s tracks, above cited.

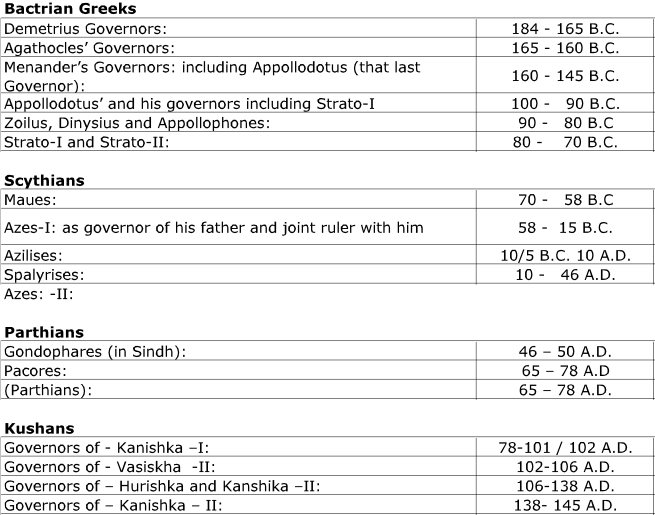

Bactrian Greeks (187-80 S.C.), Scythians (80 B.C. 46 A.D.),

Parthians (46-78 A.D.) and Kushans (65-176 A.D.) in Sindh.

There has been very little work done on this period of Sindh’s history since Independence. Lambricks[14] work is too sketchy, three works by Tarn[15] Marain[16] and Woodcock[17] produced in fifties are the only authorities making use of numismatics. Mujamdar

And Munshi[18] by making use of pre-independence sources have re-constructed the chronology of kings of various dynasties. A recent article of Dr. Dani[19] is another source based on numismatics.

Post-independence archaeological explorations are limited to Banbhore, where the bottom layers go first country B.C.A number of objects[20] of this period and coins were un-earthed. Dr. F.A. Khan states that because of high water table he could not dig deeper. In his opinion this settlement may well have been Alexander’s Heaven, the port through which the fleet of Nearchus entered the Sea. Lambrick’s map of Buddhist sites, the first to seventh centuries A.D., based on pre-independence sources especially Henry Cousin[21].

While this article was being sent to press, the daily Dawn on May 18th 1985, reported a new settlement oposite to Banbhore and of the same age on an island. Present writer is of the opinion that there is gorge of the rive Indus between Banbhore and this island. The gorge seems to have trapped a branch of the Indus and held there probably between 4th century B.C. and 13th Century A.D.

The present writer[22] used all these sources, except ref. No.109 to buildup the history of the period and has covered the material in 18 pages. The various rulers of Sindh and the period of their rule was as under:-

During this period Kushans held the northern Sindh only. The lower Sindh was ruled by Parthians: 78-135 A.D; Scythians: 135-145 A.D. and Parthians: 145-176 A.D.

Small independent principalities ruled Sindh from 176-283 A.D.[23].

Sassanians: (283-167) A.D.

Hitherto it was thought that Sassanians ruled Sindh from 283-632 A.D. and Rai Dynasty of Sindh were their governors. Close examination of the all available and scattered sources mostly of Pre-independence period has revealed otherwise. The present writer; has collected this material and presented in 6 pages. Sindh was ruled by an independent principality of Vahlikas from 376-415 A.D. and again by some other principality independently upto 499. A.D., when Rai Dynasty established themselves. Most of the known Buddhist stupas (in ruins) in Sindh were constructed between 200-500 A.D.

Rai Dynasty 499-641 A.D.

The basic information on this dynasty still comes from Chach Namah. The first Arab Naval expedition was sent against the subcontinent in 637 A.D. Chronology of Chach-Namah is defective. Hieun Tswang, who visited Sindh saw a Sudra king (Rai Sehasi-II) ruling Sindh between 630-641 A.D. Chach therefore could not have come to power until 641 A.D. That Sindh was independent in 617 A.D. is known from Sindh’s king sending his ambassadors with a congratulatory message to Roman Heraclius on his defeating Khusro Parwez at Naina. The present writer has collected all scattered pre-Independence sources for supplementing the information and had revised the chronology of rain and Brahman dynasties[24]. Lambrick has also done full justice to his chapter of Sindh’s history[25]. Chach-Namah Sindhi translation has useful notes by Dr. N.A Balouch[26], based on Daudpota’s Chach Nama (persian text), Haig (Ref. 12), Raverty (Ref.2), elliot and others.

.

Brahman Dynasty 641-712 A.D. and 715-725 A.D. the eastern Sindh only.

Chach-Namah’s Sindhi translation with notes 118 gives basic information on this dynasty, however Mujamdars[27] Arab conquest of Sindh has lot new information. He had used a number of original Arab sources. Lambrick[28] had analysed causes of the down fall of Brahman dynasty. He has also produced a good map of the routs of Arab conquest.

The present writer has used all these sources as well as the original sources to re-construct Brahman rule and Arab conquest of Sindh in 711-714 A.D.[29], Williams has revealed that Cutch formed part of Rai and Brahman Sindh from about 500 A.D. to about 685 or 696 when it was lost to Chawras[30]. The river Indus changed its course around 685-700 A.D., deserting the Lower Sindh. Kathias, a local tribe from Sindh, moved to Cutch and from thence to Kathiawar around 700 A.D. Since the lower Sindh was depopulated, it made the Arab conquest of the Lower and South –western Sindh easy and with-out any resistance[31].

In view of all this new and systematic material it is now possible to rewrite a complete history of Rai and Brahman dynasties and circumstances leading to Arab conquest of Sindh, when it happened after failures of first fourteen invasions over a period of more than 50 years.

The work on this subject was initiated by Dr. Daudpotta in the Persian texts of Chach Namah and Masumi in 1938 and 1940 as already mentioned. These sources were used by Syed Abu Zafar Nadvi to write history of Sindh. It was the first attempt to write history of the Arab governors of Sindh and with analysis of events. The author has done many blunders and distortions and his historical maps are totally in-accurate and un-intelligible[32]. Memon Abdul Majeed has probably used this as the only source for his Sindh and Multan’s Arab governors and has repeated the same chronological mistakes,[33], but it formed definite information for Sindhi scholars as Nadvi’s book was not readily available. Dr. Mumtaz Pathan is the first scholar, who used all scattered material on Arab rule of Sindh. His work so for is the best document on this subject[34]. Dr. N.A. Balouch in his various articles as well as notes on Masummi has referred to Arab governors’ rule of Sindh, but this material is scattered and required re-compilation[35]. R.C. Mujamdar has given references to many new Indian sources on his successors. This new information collected from inscriptions and some contemporary Sanskrit and Gujarati works, has merit of its own[36]. There is also some material in the Archaeological Survey of India’s reports, Bombay Gazetteers/Annals and Histories of Gujarat and finally writings of Arab travellers and merchants.

The present writer made use of all available material, had Arab.

Sources re-verified with the original texts and put all the events in a chronological order[37]. In view of this new material, is possible to re-write this chapter of Sindh’s history.

Archaeological Department of Pakistan has carried out excavation at Banbhore and Brahmanabad-Mansura site. On the first site final report has been issued, work on second site is in progress[38], although in 1979 the dept. issued an official statement that Brahmanabad / Mansura is same site.

Habari Rule of Sindh (854-1011 A.D.)

Dr. Daudpotta had worked out chronological rule of Habaris in notes on Masumi in 1938. This material was utilized by Nadvi to write history of Habaris[39], but the latter work is far from satisfactory and same is case of Memon Abdul Majeed[40]. Dr. Mumtaz Pathan’s Arab kingdom of Mansura is upto date work on the subject. Habaris with the active help of local tribes ruled successfully for 171 years and had maintained good relations with Gujarat, Pratiharas (of Rajasthan, Uttar Pardesh, Bihar and Northern Madhya Pardesh), Rashkuttas of Maharshtra and Hyderabad (Dn). They managed to have good relations with Hindu Shahi rulers of the Punjab; Sammas of Multan and Hindu Sammas and Chawra rulers of Cutch. The political and economic conditions of the period for other areas of Sub-continent are also well known. Present writer was able to locate the courses of the river Indus in the 9th century and from it worked out possible areas under cultivation, as well as the population[41]. A large number of travellers, geographers and merchants, mostly of Persian origin (but popularly called Arab geographers) visited Sindh as well as the Sub-continent and wrote accounts specially pertaining to local produce industry, exportable commodities and etc. These accounts await a full analysis by historical economists. The present writer has covered their chronology in 24 pages and has the guidance of future writers[42].

Soomra Dynasty (1011-1351)

As already mentioned, the sources of original information on Soomra dynasty was Tarikh-i-Bahadur Shahi, which is now lost. This work was used by Firshta, Abul Fazal, Khan-e-Khana, Nizamuddin, Masumi and many other Persian historians of late 16th and early 17th century to write Samma-Soomra history. The Archaeological department of Pakistan had undertaken a survey of Soomra-Samma ruined towns and settlement in Sindh at my request in sixties and large numbers of sites have been located[43], but no explorations have been done. Dr. N. A. Balouch had made serious efforts to build Soomra history from the folk-lore, was written in 15th and 16th centuries and is not a sober history. Besides, Marvi, Laila and Mumal etc. are fictional beings having no real existence. Certain incidents are however too well known and present writer used this material to reconstruct Soomra history:-

A few notes worthy points are:

i. Soomras were Ismailis, was already known, but Abbas H. Hamadani has collected all possible information[44].

ii. Upto 1714 A.D., Soomras practiced lot of Hindu customs[45].

iii. Daulat-i-Alviya a history of Soomras is a forged and unreliable source on Soomras.

iv. That Mahmud of Gaznavi sacked Mansura in 1026 A.D. was already known from works under-taken by Nazim and Habib. Dr. Mumtaz has used same sources to prove this point, but department of archaeology’s statement in “Dawan” should be considered as the last word that Mahmud sacked and burnt Mansura.

v. Mahmud’s army being looted by Jatts of northern Sindh and his avenging on them in 1027-28 is no longer being doubted. Earlier version that Jatts belonged to northern Punjab is no longer valid.

vi. That Sindh remained part of Gaznavid Empire upto 1281 A.D., is disproved. Sindh became independent soon after Mahmud’s death in 1030 A.D.

vii. A 16th century history of Soomras called Muntakhab-ul-Tawarikh by Muhammad Yousif belonging to Maulana Qasimi was reprinted in his foot notes on Tuhfatul-Kiram by Hassamuddin, is a new source and has been helpful in writing Soomra genealogy and adding to our knowledge of Soomra period.

viii. Ismaili sources and biographers of their preachers have also added to our knowledge of Soomra period.

ix. Historians of Gujarat and Rajasthan have also given some information on relations of those States with Sindh, but this information is not fully explored[46].

x. The Persian Historians of Delhi and Mongols, too have given some references to Sindh. These have been tapped to connect a chain of incidents. Such historians are: Tabqat-i-Nasiri, Mubarak-Shahi, Mirat-i-Sikandri, Mirat-i-Ahmedi, Zainul-Akbar, Ibn Asir, Tarikh-i-Utbi, Diwan-i-Farrukhi, Tarikh-i-Behaqi, Al-Abad Saghani’s Taj ul-Masasir (Arabic), Ain-i-Haqiqat namah, Jahan-gusha-i-Juwaini, Rehala of Ibn Battuta, tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi of Barani, Tughlaq name of Amir Khusru, Jami-ul-Tawarikh of Hamadani, and Masalikul absar of Abu-Safa-Sirajuddin Umar.

xi. Jalaluddin Khawarizm Shah after having been defeated by Chengiz Khan was chased by him right upto Attack. The former came to Sindh, sacked Sehwan and burnt Debal, Pari Nagar and some towns in Kathiawar to collect wealth, to re-conquer the lost territories. Chanesar was ruler then.

xii. Ibn Battuta visited Sindh in 1333 A.D., and saw Samma’s rebellion against Delhi government.

xiii. Mohammad Bin Tughlaq took an expedition against Soomras but probably was poisoned and died at Sondha. The imperial troops were chased and looted by Soomras.

The present writer has collected all above material and has reconstructed a history of Soomra over 104 pages[47] discarding folk-lore altogether.

It is possible to collect material on the same lines especially from areas around Sindh to add to our knowledge of Soomras of Sindh. Archaeological explorations can throw light on arts, crafts, economics and day to day life of this period.

Samma Dynasty (1351 – 1224 A.D.)

The situation on Samma period is exactly the same as Soomra Period. Its original source being Tarikh-i-Bahadur Shahi, now lost, from which same histories were copied as mentioned in first paragraph of (v) above. The material being scanty the present writer has made efforts to co-relate various incidents chronologically, to make a continuous chain of events with encouraging results. Luckily for us there are some outside sources of information, for example.

i. Battuta’s visit to Sindh in 1333 A.D. and seeing Sammas under Unar, rebellion[48].

ii. Mohammad Bin Tughlaq’s expedition on Sindh in 1351 A.D. and death at Sondha is better known from various sources including Mahdi-Hussain Agha[49] and 14th century historian Ziauddin Barani’s Tarikh-i-feroz Shahi. That he was poisoned to death is elaborated by Mahdi Hassan. His temporary burial at Sehwan for the first time discovered by Professor Muhammad Shafi in 1935[50], was brought to the notice of Sindhis by Dr. Daudpotta’s Masumi in 1938. It has been reproduced by many scholars in various journals including Alwahid’s “Sindh Azad Number” in 1936.

iii. The Samma’s overthrew Soomras soon after 1335 A.D. and the last Soomra ruler took shelter with Feroz Shah’s governor of Gujarat is known from “Insha-e-Mahru, a collection of 101 letters of Mahru, the governor of Multan and a master mind of his age[51]. Mahru managed that Feroze-Shah may take expedition against Sindh to restore Hamir Dodo. Preparation started in 1364 A.D., and in 1365 having lost the battle with Sammas and 5000 boats destroyed by Cutchi seamen, the Sultan left for Gujarat via Cutch, where Cutchi guerillas attacked and destroyed his whole army[52]. With new re-inforcements he marched on Sindh, via the desert in September 1366 A.D. and lost battle after one year in October 1367 A.D. but with new inforcements from Delhi and putting Makhdoom Jehania of Uch as mediator, he made Banbhiniyo to surrender[53]. That this Makhdoom came to the rescue of Feroz Shah three or four times bringing compromise between Delhi and Sammas to the advantage of Sultan, is brilliantly described by Dr. Riazul-Islam[54]. This work of Riazul-Islam covers Samma period upto 1388 A.D.

iv. On Ferozshah’s death, Delhi Sultanate disintegrated and Sammas became independent. The chronology of Sammas first worked out by Hodiwala[55] in 1939 was corrected by Dr. Balouch[56]. The present writer re-verified the original sources and has revised the above two version[57]. Hassamuddin in Tarkhan-Nama and Tuhfatul Kiram has used Dr. Balouch’s chronology with acknowledgements[58].

v. Information on Sammas from 1386 – 1508 is very scanty and scattered sources like Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi by Afif, Frishta, Masumi, Mubarak-Shahi, Tabqat-i-Akbari, Tahiri, Mazahar Shah Jehani, Tarkhan Namah, History and Culture of Indian People. Vol. IV, Tarikh-i-Shahi, Maraat-i-Sikandri, Maraat-i-Ahmedi, Tuhfatul-Kiram, Todd’s Rajasthan, Ain-i-Akbari, Maathir-i-Rahimi and Hadiqatual-Aulia have all been tapped by the present writer to cover this period in 28 pages[59]. Three other sources little known in Sindh on this period are Zafarul Walih[60] Bahawalpur District Gazetteer[61], and Subuh-al-Asga[62].

vi. On Sindh-Gujarat and Sindh-cutch relations, Miraat-i-Ahmedi[63], Maraat-i-Sikandri[64] and William’s Black Hills throw new light, which shows that due to interference of Jam Feroz into a dispute between two ruling cousins of cutch, the aggrieved party Rao Khenghar helped Jam Salahuddin twice, first time to over throw Feroz and next time to fight Shah Hassan and Shah Beg, who had restored Feroz. Later he helped Feroz to fight Arghoons. Cambridge History of India[65] and Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency[66] give information about Jam of Nizamuddin’s period.

Nizamuddin’s period.

vii. On Samma’s down-fall (1508-1524), besides Williams and other sources are mentioned in (IV) and (V) above, Tuzuk Babri, or Babur Nama in another important document.

viii. Chronology of the period from 1508 to 1524 A.D. as given by Masumi is defective. This has been corrected by Dr. M.H. Siddiqi. He also has describes Balouch migration to Sindh during the same period in one appendix. Dr. Siddiqi also describes Mehdi Jaunpur’s mission to Sindh in 1501-1503 A.D. The failure of this mission and sinking of his boats by Hyder Shah of Sann at the instruction of Makhdoom Bilawal is described by G.M. Sayed.

Pakistan’s Archaeological Dept. has done virtually no work on this period, except a single season’s survey mentioned in Ref. (44). Ghafur wrote on calligraphers of Thatta, a work of minor importance and two monographs on Thatta by Shamasuddin and Siddiqi Idris, were published by the Deptt. Of Archaeology. The department helped Hassamuddin with a large number of photographs for his Makli Nama and Tuhfatul-Kiram. Dr. Dani’s Thatta, is based on Hassamuddin’s work. Hassamuddin used Khan Khudadad Khan Persian manuscript ‘Biaz’ for Makli Nama. Baiz[67] has sketches of graves with sketches of inscriptions and also inscriptions re-written in plain Persian alphabet for convenience. The post-independence archaeological work on the Samma period of Sindh therefore may be considered as almost nil and we have to revert back to Cousens ‘Antiquities of Sindh’, actually written in 1908-09, but printed in 1925.

Arghoon (1524-1554) Tarkhans 1554-1591 and Mughals (1587-1736 A.D.)

Information on this period before the independence was scanty. All credit for work on this period goes to Sindhi Adabi Board, who published a large number of Persian history tests, poetical works giving references on Sindh and a number of articles in Jour. Mehran. Of the prominent scholars who did this work the out-standing were Hassamuddin Rashdi and Dr. N.A Balouch. The former has specialized in the Mughal period of History of Sindh and more than 90% of his work on Sindh was on this period i.e. 1500-1750 A.D[68]

In various books Hassamuddin has given elaborate footnotes from contemporary historians mostly of the Mughal court. His Urdu and Persian works published by other organizations do not pertain to Sindh, but all the same belong mostly to the Mughal period. He has almost exhausted all known material on Sindh in Persian, written on the period 1500-1700 A.D., as most of material available pertains to Kalhora period and he had not specialized in it.

Dr. N.A. Balouch, essentially a scholar of Sindhi language and Sindhi folk lore, has been writing on arts and crafts of Sindh and some biographical Sketches. He edited two Persian historical works for Sindhi Adabi Board and wrote exhaustive notes on Chach-Namah and Masumi. He also wrote on some archaeological sites, but limiting himself to history of the place rather than archaeology[69]. These two scholars have remained on the fore-front in research on history of Sindh. Although Hassamuddin exhausted almost all Persian sources of this period, he did not touch English and European sources. Plentiful work has been done in English on Mughal administration, economic conditions foreign trade, foreign relations European travellers’ accounts and provincial administration of the Mughals, but as the specialist on Persian sources of Sindh’s History, he has eliminated them altogether, except occasional references to Haig and a few others. In his notes on the Persian texts most of which are in Sindhi, he has given quotations from Persian texts but these quotations have not been translated. Makli Nama which has 90 pages of Persian text and more than 700 pages of the notes in Sindhi is a monumental work. The Persian text in un-translated and is still in original form. Sindhi Adabi Board published Mazhar-Shah-Jehani, translated into Sindhi and book soon went out of stock. Unless this vast material on this period of Sindh’s past is translated, the young historians ignorant of Persian can not make any use of it. For the analysis of Mughal rule in Sindh, European sources also have to be re-examined[70].

Dr. Balouch’s two Persian texts also belong to this period of Sindh’s history and thus we are fully equipped to write an authentic history of Arghoon, Tarkhans and Mughal governors of Sindh.

On the examination of histories of the period specially Mazhar Shah Jehani and Beglar Nama, British factory records (1635-1662) and European travelers’ accounts, one finds that this was the period of great turmoil. Sindhis from the Urban areas, specially Ulama and business men had migrated to Cutch, Gujarat, Burhanpur and Arabia. The Arghoon had deliberately forced the population to quit the Urban areas to create place for their own people, who under pressures of Babur had to leave their own settlements in Central Asia and Afghanistan. During the Tarkhan period Sindhis started a kind of civil war, which continued through, up to Kalhora take over. Present writer has published detailed article on this civil war[71]. This could also be looked from the other angle of ruling class of the period and every action may be justified on the basis of local’s rebellion against the government. Dr. Zahid Ahmed Khan has approached the Subject from that angle[72].

These two views need critical examination by a third party, but the fact was that there was no peace during the period and the economy had dwindled, marking it easy for Kalhoras take over in the very life time of Aurangzeb.

Kalhoras dynasty (1700-1783)

As stated earlier there was plenty of scattered material on Kalhoras period mostly in the form of manuscripts, but no history based on even on fragmentary material exited. Qani’s Tuhfatul Kiram had only a few pages on Kalhoras. Sindhi Adabi Board assigned this job to Ghullam Rasool Mahar and published ‘A history of Kalhoras’ in 2 volumes. He used a very large number of Persian and English sources to construct the history of Kalhoras. The author has done some justice to the subject, specially looking to the vast material thus collected in historical sequence[73].

Dr. Riazul-Islam has now published two volumes of correspondence on Mughal and Nadir Shah’s court. This throws new light on the subject and needs a new thinking, McMurdo Waiqia-i-Sindh or History of Kalhoras has also gone unnoticed by Mahar. Dr. Balock N.A’s. ‘The last of Kalhora Princes of Sindh[74], was not known to Mahar. Mahar also has failed to analyse economic circumstances leading to the disintegration of he Mughal Empire, which led to Kalhoras quick rise to power. Economic conditions have not been properly looked into. The Sufi movements, which rose in 16th and 17th century to counter, balance the ritualistic religious group, have been over-looked. It is 28 years, since the book was first published and there is a need for a new version of history of Kalhoras. The sanads and letters of Kalhoras available in manuscript form are another large source of material on this period.

In the field of archaeology, no work has been done on this period. The leading Baouch Sardars, who came with Mian Nasir, are all buried near Gharhi at Mian Nasir’s grave yard. Their descendents too were being buried there, until the first half of this century. This major grave yard needs an archaeologist eye and reconstruction of the history.

Talpur rule of Sindh 1783-1843

Sindhi Adabi Board has published Azim’s ‘Fateh Nama’ a poetical work on the Civil War leading to the down-fall of Kalhoras and rise of Talpurs. The study of economic conditions of Sindh during the Kalhoras period shows that in 1758 A.D., the area under cultivation in Sindh was 22 lakh acres and population 30 lakhs. During this year there was a major change in the course of the river Indus, which abandoned its course near Hala and taking the present course west of Hyderabad. Earlier it was flowing from Hala to Odero Lal, Shaikh Bhirkio, Tando Muhammad Khan, Matli and Badin to Koree Creek. This major change put 10 lakh acres out of cultivation. People were up-rooted. Building of new canals would take many years patience. Such changes invariably have brought changes of dynasties in the past. The resulting strife due to this change was in form of civil-war between Noor Muhammad Kalhoras sons, where Ghullam Shah with support of Balouch Sardars was installed as ruler. Subsequent events were simply strife to hold the cultivable land. It finally ended in change of the government from Kalhoras to Talpurs in 1738 A.D.

The new rulers soon got involved into an international political triangle. Since 1783 Russia has started expanding towards India and British from Calcutta had started a move west-ward. By 1799 it was clear that the two powers were to have a clash. The British planned to reach the Indus at the earliest and later on planned to meet Russians at Oxus or beyond. Sindh and Punjab had to be subdued. The major part of Talpur history therefore is their relations with the British. Many writers like Advani, Mariwala and Mirchandani wrote on British designs on Sindh. This prepared a way for collection of source material on Sindh. Khera Published a small book on the subject from Lahore in 1946, but detailed work was yet to be done. The first work after independence was of Lambrick’s[75].

In this scholarly work the learned author unbiasly has described Talpur-British relations from 1799-1843, leading to conquest of Sindh and details of the Sindh battles: Huttenback[76] was next author to elaborate this work further. He was able to use India office records in London in more details than Lambrick. Truly as the title suggests, it was dissection of Imperial designs. He correctly identified relations in 5 phases[77].

Dr. Duarte who had also written on the same subject in early fifties, tried desperately to have his book published but its publication was blocked on the basis of being biased and favourable to the British. The book was not published until at orders of the late Mr. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1976[78]. Meantime Kala Therani using mostly records from Archives of India, published yet another book[79].

Two other books by Gillard[80] and Khan[81]gives yet another version of the necessity of British conquest of Sindh and major factors involve. In terms of material, the studies done are concrete and there seems nothing new to be added to this subject unless new records come to light. The history of Talpur period is still to be written. Scattered articles, some of scholarly merit like Duarte’s ‘Court of Talpurs[82], Karachi Mirza Gul Hassan Beg’s literary persuits of Talpurs[83], Hassamuddin’s Seals of Talpurs’[84], and Mayer L.A’s Islamic armours and their work, Geneva (1963), depicts Talpur swords. These are but a few of many standard articles. Talpur correspondence, letters, Sanads and etc. in manuscript form exist with various families, individuals and institutes.

Many Talpur have family records. The ruling families museum is another collection of arts and crafts of the period. History of alienation and history of Jagirs form vast material on the period and so are early British records bluebooks, reports and travellers documents.

All this scattered material could be collected, translated and published to form source material for study of this period.

British Period. (1843-1947 A.D.)

This is so recent a period and there is so much material available that there should have been a maximum number of publications on it. Unfortunately this is not the case. Since independence, only first 16 years of British rule are covered to some extent by two books of Lambrick ‘Charles Napier and Sindh’ and ‘John Jacob of Jaccobabad[85], and Dr. Hamida Khuhro’s[86] Making of Modern Sindh’, which is dissertation on Sir Bartle Frere’s administration of Sindh from 1251-1859. Other works of some merit are on the separation of Sindh from Bombay presidency by G.M. Sayed[87] and Ph.D. Thesis of Saheb Dino Chana[88]. To these may also be aded Hamida Khhro’s collection of documents on the same subject in two volumes[89].

The rest of period is a large vacuum. A number of books written by British and Western writers discuss this period of Sindh’s history in different context or bio-graphies but these may be considered only the source material. In the same way four bio-graphics by G. M . Sayed[90].

All Muhammad Rashdi[91], Kairm Baksh Nazamani[92] and Hassamuddin Rashdi[93] are only source material for use of future historians. The Gazetteers were used as ready beckoners. One such Gazetteer by Sorley was published by the Government of West Pakistan, in 1969. It is history of the British administration of Sindh from 1905 to 1947[94], The West Pakistan editors of this Gazetteer took liberty of changing the text or expurgating portions of it. Thus we no longer have the benefit of knowing some important observations of author on working of provincial administration of Sindh since 1935 and also his own observations on the circumstances leading to formation of Pakistan.

In any case the book is indispensable for the histories of the British period from 1805-1947. Aitkin’s Gazetteer of Sindh, first printed in 1907, and has recently been reproduced by Indus Publishers, Karachi, with an introduction by Mazhar Yusuf, who is also Honey. Editor of the Sindhological Studies, from the very inception of the Journal[95].

During the period there were a number of political, social, and religious movements, for example.-

1. Hur movements, of 1890-1900, 1910-15, 1941-47.

2. Khilafat Movement, 1917-1924.

3. Separation of Sindh movement 1913-1933.

4. Muslim League and Pakistan Movement. 1938-1947.

No complete history of above movements has yet been written.

Lambricks,[96] books on Hurs is information as the British officials saw and thought of the movement.

The British period records are well preserved in the India office Library in form of numerous reports. One important series of the reports was “Annual administrative report of the Bombay Presidency from 1861-1933 and thence after there were annual administrative reports of each department of province of Sindh.

Another series of the reports was “Revised Survey and settlement reports of each Taluka of the province” issued every 10th year since 1871 to 1932. The report gave crops cropped areas, irrigated areas, population of each Taluka. The census reports besides statistics give important information on language, ethnic groups, castes and tribes. All these reports are rare in Sindh but are preserved in the India Office Library.

In 1982, the Irrigation Department of Sindh invited scholars and engineers to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Sukkur Barrage and to write on the history and impact of Sukkur Barrage. These papers are being printed in two volumes by the department and they cover the complete history of irrigation during the British period.

The present writer has listed the names of reports of the British period, mostly available with him, in ‘Source Material on Sindh[97] and maps of Sindh in the India Official Library, British Museum, Royal Geographical Society and Archives of India.

Debates of Bombay Legislature 1923-1935, Sindh Assembly 1937-1947, is another source and so are the Round Table Conference proceedings. In fact the detailed history of developments in each government department and institute needs to be written. The above information is given as a guide line for scholars interested in writing the history of British Rule in Sindh.

British developed a new type of architecture in Sindh for their offices, schools, public utilities etc. Under them the private owners for their buildings in the towns also adopted a new type of architecture. Some of these buildings are monuments worth preserving but they are being pulled down by the owners as well as governmental agencies. This amounts to destruction of our history as much as destruction of our archaeological sites. No engineer has come forward to write on British architecture in Sindh, its evolution, maturity and special features. This should form top priority for our historians. The daily ‘Evening Star’ has started a crusade to save Karachi’s huildings from destruction. 5000 private and government buildings will form part of this project. The work has not been extended to Sindh, where even in the rural areas Wadera’s Autaq was a copy of either a school or an office building.

It is interesting to note that all government buildings before 1880 A.D., used wood beams and raftars. After 1880 A.D., they switched over to girders, T-irons and brick tiles or wooden planks. Reinforced concrete was not introduced until 1915, but its use on a wide scale came after 1930. It did not reach rural Sindh until after independence.

A large number of books on British officials life in Sindh, administration of India, military operations and management, their way of living, letters from India back home, paintings and etc. have appeared in England. These too are very rare sources of information on Sindh[98].

References

[1] Herodotus, ‘Histories’, translation Aubrey de Selincourt, London, 1945

[2] Archaeological Survey of India, ‘Naksh-i-Rustam Inscriptions’. New Delhi, 1925, mentions that Sindh was part of Darius-I’s Empire. Journal Royal Asiatic society’ of Great Britain vol-Z. P. 294, mentions annexation of Sindh. The Behistan inscription of 520 B.C. mentions Gandhara as part of Darius’ Empire, but not Sindh. Persipolis inscription is dated 520 B.C. and Nakshi-Rustam 518 B.C. Annexation of Sindh, therefore, took place in 519 B.C.

[3] Olmslead A.T. ‘History of Persian Empire,’ Chicago Univ. Press, 1948.

[4] Ghirshman, R. ‘Iran’. London, 1954.

[5] Robin Fox Lane, ‘Alexander the Great’, London, 1970, and On Alexander’s tracks, London, 1982.

[6] McCrindle John Watson. The invasion of India by Alexander the great gives full translation of these five historians. Sindh V.A. in early history of India London 1908 Summarizes last five sources on Alexander in India. The latter was the only authentic source on Sindh before Lambrick but was sketchy. M.H. Panhwar in “22 classical Greek and Roman write ………….. Sindh” Mehran. Vol-30, 102, pp. 108-139 has described the first three original historians of Alexander

[7] Same as Ref. 53 and 54.

[8] Same as Ref. 55.

[9] Smith, V.A., ‘The early history of India,’ Oxford 1908, and Asoka the Buddhist Emperor of India; revised edition. 1920.

[10] Rapson M.A., ‘The Cambridge history of India,’Vol-I Ancient India. 2nd edition New Delhi, 1962.

[11] Mookerjee in Munshi K.M.(ed)., ‘History and Culture of Indian People’, Vol-II. Pp. 58-105, Bombay, 1953.

[12] Same as Ref. 55.and Eggermont on ‘Asoka’s inscriptions.’

[13] Lambrick H.T. ‘History of Sindh series, Vol-II,’ 1973.

[14] Same as Ref: (103).

[15] Tarn, W.W. ‘Greeks in Bacteria and India,’ second editions, Cambridge University Press, 1959, and Hellenistic Civilzation, London, 1941.

[16] Narain, A.K. ‘Indo Greeks, Oxford. 1957.

[17] Woodcok, George, ‘The Greeks in India.’ London, 1955.

[18] Mujamdar R.C., in Munshi (ed). The History of the Indian People’, Vol. II, Bombay, 1953.

[19] Dr. Dani A.H.

[20] Same as ref. (41).

[21] Same as re. (103) and Henry Cousins. ‘Antiquities of Sindh’, Calcutta, 1925.

[22] M.H. Panhwar ‘Chronological Dictionary of Sindh’, 1983, pp, 90-108, charts and maps numbers 17-26 and figures numbers 65-73. Dr. Dani’s findings, which were published later on will not change the above chronology of the rules. Sindh was ruled by small independent principalities from 176-283 A.D. when Sassanians conquered.

[23] Same as ref. (112).

[24] Same as ref. (112) pp. 108-113; chart and map number 29.31 and 32 and figures 74-82

[25] Same as ref. (112) pp. 115-112 and chart and map numbers 33 and 34.

[26] Same as ref (103) Dr. N.A. Baloch’s Notes on Makhdoom Amir Muhammad’s Chach Namah. Sindhi Adabi Board, 1945. 117 & 118 same as ref. (116), Dr. Baloch’s Notes etc

[27] R.C.Mujamandar Arab Conquest of Sindh. Jour Asiatic Soc. of Pakistan, Dacca, 1948.

[28] Same as ref. (103).

[29] Same as ref. 112 pp. 123-143, chart and map numbers 34-37.

[30] Williams, Rush brook, ‘The Black Hills. Cutch in History and Legend’ London. 1958.

[31] M.H. Panhwar, ‘Sindh-Cutch Relations, ‘Karachi 1980. The 5000 years of irrigation in Sindh (in press).

[32] Arab rule of Sindh, Umayyad (714-749 A.D.) and Abbasid (751-785 A.D.). Governors.

[33] Memon Abdul Majeed Sindhi, Jour Mehran, No. 2 & 3 , 1961 pp. 137-168. 1 pp. 137-168.

[34] Dr. Mumtaz Pathan, History of Sindh Series Vol-III. ‘The Arab Period, Sindhi Adabi Board, 1978.

[35] Balouch Dr. N.A. ‘The most probable site of Debal’, the famous historic part of Sindh, Islamic Culture, Vol. XXXI, No. 3. 1952. pp. 41-49. Also notes an Sindhi translation of Tarikhi Masumi, Sindhi Adabi Board, 1956.

[36] R.C. Mujamdar, same as Ref. (119) Also ‘History and culture of Indian People,’ vol-III, pp. 57-164, vol-II, p. 130, Vol-IV, pp. 20, 99, 106, 115, 126, 272, 467 and 353.

[37] Panhwar M.H., ‘Chronological Dictionary of Sindh,’ pp. 143-183 and char numbers 38-39. Also Sindh Quarterly, December 1976.

[38] F.A. Khan, same as re. 41. Archaeological Deptt’s report same as ref. 46.

[39] Same as ref. (124).

[40] Same as ref. (125).

[41] Same as ref. (80).

[42] Same as ref. 129. pp. 183-206 and chart and maps, numbers 40-44.

[43] Same as ref. (44) . While levelling of land by bulldozers in Kotri Barrage, I came across many ruined settlements in 1961-64. These were reported to Dr. F.A. Khan of Archaeological department

[44] Hamdani Al-Abbas H., ‘The Beginings of Ismaili Dawa in the Northern India,’ Cairo, 1956.

[45] Ali Muhammad Khan, ‘Mirat-i-Ahmedi,’ english tr. Nawab Ali and Seddon, Bombay, 1928. Persian text, Baroda, 1928. Earlier English trans. By J.Bird, London 1938. Urdu tr. Zafar Nadvi 1933.

[46] Such sources are: ‘Jhala Vanish Yarkh Kara’ by Nathu Ram: ‘Deyasreyakpva’ of Hemachandra; R.C. Mujamdar’s Chulkayas of Gujarat’, rushbook’s ‘Black Hills’, Kilikanmudo of Somevera; Rai Bahadur Gauru Shankar Ojha’s ‘History of Rajpootana’ and etc.

[47] Same as Ref. 129 pp. 206-310 and charts and maps numbers 45-51.

[48] Ibn Battuta, ‘travels,’ volume, III, by H.A.R. Gib, London, 1973, is the latest work in his travels in Sindh and has removed many of previous misgivings on historical geography of the period. Based on this M.H. Panhwar has given map of the possible route of Battuta’s travels in Sindh, in chronological dictionary of Sindh.

[49] Mehdi Hussain Agha, ‘Tughlaq Dynasty,’ Calcutta, 1964, and Rise and fall of Muhammad Bin tughlaq, Ain-i-Haqiqat Namah and futuh-us-Salatin of Isami, describe Tughi’s Rebellion and Muhammad tughlaq’s action.

[50] Mohammad Shafi, ‘Oriental College Magazine’, Vol-II, No. 1, 1935, pp. 156-161

[51] Mahru, Ain-al-Malik, ‘Insha-e-Mahru’ (Persian), Text edited by Shaikh Abdur-Rashid and Dr. Muhammad Bashir, Lahore 1965. Letters pertaining to Sindh (except one) are reproduced in Makli Namah by Sayed Hassamuddin, but without Sindhi translation.

[52] Williams Rushbrooks, same as ref. (122).

[53] The various sources have been collected and compiled in chronologically by M.H. Panhwar, in ‘Chronological Dictionary of Sindh’, pp. 316-328.

[54] Riazul-Islam ‘A Review of reign of Feroz Shah’, Islamic Culture, Vol-XXIII, 1949 and ‘Sammas rule in Sindh’, Islamic culture, October, 1948. Futuhat-i-Feroz Shahi, ‘Islamic Culture’, 1941, has also been tapped by Riazul Islam.

[55] Hadiwala Shahpur ji Harmasji, ‘Studies in Indo-Muslim History,’ Vol-I, 1939.

[56] Dr. Balouch N.A., ‘Chronology of Samma rulers of Sindh’, Pakistan Historical Records and Archives Commission, Karachi 1957 also in notes on Tarikh-i-Tahri of Niyasi, Sindhi Adabi Board. 1964.

[57] Panhwar M.H. ‘Chronological Dictionary’ of Sindh p. 265 and details in respective years

[58] Sayed Hassamuddin Rashdi (ed), ‘Tuhfatul Kiram’, vol. III, Part I Persian text, 1971, and also Tarkhan Name (ed)., 1965. both by Sindhi Adabi Board.

[59] Same as 149, pp. 337-365.

[60] Dabir, Hiji Abu Turab, ‘Arabic History of Gujarat’ Ed. Davison Ross, 3 volumes,Leyden, 1911, 1929.

[61] ‘Bahawalpur District Gazetteer’, Vol- XXXVI-A, 1903 by Barnes and Minchin

[62] Ahal Abbas Shahbuddin Ahmed Qalqashandi, ‘Subuh-al-Asha,’ Cairo. 1913-20.

[63] Ali Ahmed Khan’s, Mirat-i-Ahmedi, Baroda. 1928.

[64] Faridi, Fazullah, ‘Mirat-i-Sikandri’, Engl. Tr. Bombay 1930.

[65] Vol-V. p. 306.

[66] Vol V. ‘Cutch Palanpur and Mahi Kantar’, p. 91

[67] Khan Khudadad Khan, ‘Biaz’ (MS); In possession of Hassamuddin Rashdi, and reproduced in Makli Namah.

[68] Syed Hassamuddin Rashdi edited following Persian texts for Sindhi Adabi Board (1) Mathnavi Chanesar Nama of Idarki Belgari (written 1510 A.D.). 1956: Mathnavi Maazaharul-Athar of Shah Jehan Hashmi (d. 1547 A.D.). 1956; Maqalati- Shuira of Qani (d. 1788 A.D.), but 95% ofpoetry pertains to pre-1750 A.D. period); 1957 Taqmila Maqalat-i-Shujra of Muhammad Ibrahim Khalik (d. in 1317 A.H. OR 1899-1900 A.D) More than 60% poetry beloong to pre 1750 period); 1958: mathnaviat-wa Qasaid Qani, by Qani (d. 1788), 1961, Mazahar Shah; Jehani (written in 1634 A.D), 1962; Diwan Muhsan Thattvi (1121-1163 A.H. or /708/09-1749 A.D.1963 . Manaur-Wasiat-Wa-Dastur-ulHukumat by Noor Muhammad Kalhora (d. 1753). 1964;Tarkhan-Nama by Shirazi, Syed Jamaluddin (written 1654 A.D.), 1966: Hadiqatul-Auliya by Abdul Qadir (17 century), 1967; Makli Nama by Qani (d.1788) 1967; Hasht Bihist by Abdul Hakim Atta Thattavi (d. 1706 A.D.) 1968. Tazkira Rozutu Salatin wake Jawahirul Ajaib by Fakhir Harvi (d. 1561 A.D); Tuhfatul Kiram by Qani (d. 1788) History of Sindh up to (1772 A.D). 1771 AND Tazkira Mashaikh-i-Sewistan by Ghafoor Bin Hyder Siwistani (written 1679 A.D) Mehran Vol. 23 No. 41974. His Sindhi books published by Adabi Board ware: Tazkira-Amir Khani (Biography of Mir Abdul Qasim Namkeen and Mir Abdul Baqa Amir Khan (both Mughal governors in Sindh before 1034 A.D.) and Mir Masoon Bakhri (1537-1605 A.D). His Ufdu bnook Mirza Gazi Beg Tarkhan (d. 1610 A.D), also pertains to the Mughal period. 80% of his article in Mehran covers the same period of Sindh’s history.

[69] Dr. Nabi Bakhsh Baloach edited the following Persian texts for Sindhi Adabi Board:-Tarikh-i-Tahir: of Mir Tahi Muhammad, Niyasi, 1964 Belgar Nama of Idarki Beglari (written 1626 A.D), 1976., Lub-i-Tarikh-i-Sindh of Khan Khudadad Khan, and Diwan-i- Ghullam of Nawab Ghullam Muhammad Leghari.

[70] For the details of various Persian and European sources reer: M.H. Panhwar, “Source Material on Sindh”, i.e. Arghoon and Tarkhans, Conquest of Sindh by Akbar’s imperial forces, Mughal governors, Dara Shikoh in Sindh, Dutch in Sindh. Foreign and Early European travels in Sindh and etc. pp. 442-450.

[71] Panhwar M.H., ‘Sindh’s struggle against feudalism’, Jour Sindh Quarterly, 1977 and Jour Sindhological Studies, 1978.

[72] Dr. Zahid Ahmed Khan, ‘History and Culture of people of Sindh’, Karachi 1981.

[73] Persian sources used by Mahar are:- Tuhfatul Kiram, Jawahir-i-Abbasia (MS), Mara’at-i- Daulat Abbasiya, Nawa-i-Nagar, Tarikh-i-Inshah, Guldast-i-Nauris Bahar, maqalat-i-Shuira, Maathr-ul-Kiram, Bayan-i-Waqua, Manshur-ul-Wasiat, namah-i-Naghar. Dur-i-Nadiri, Fateh Nama, Insha-i-Affrad and Frere nama, The English source used are: Haig, Atakin, Goldsmith Robert Leech, Lockhart, Frazer, Anandram Mukhalis, Khawaja Abdul Karim Kashmiri,Stein, Gazetteer of Gujarat, Postan, Aitkinson, Kaleech Beg. Advani, Mirchandani and Mariwalla.

[74] Baloch N.A. ‘The last of Kalhora Princes of Sindh,’ Sindh Univ. Research Jour- Arts Series, Vol-VIII, 1986,pp.27-68.

[75] ‘Charles Napier and Sindh’, Oxford, 1952.

[76] Huttenback Robert A, ‘British Relation with Sindh, 1799-1843-A dissection of imperialism’, Los Angeles, 1962.

[77] The five phases specified are classified as (a) Napoleon’s fear, 1799-1809 (b) Mis-under standing over Cutch, 1814, (c) Establishment of British Paramouncy. (d) Russian threat and Afghan wars. (e) Conquest of Sindh.

[78] Duarte, Dr. Adrian, ‘British Relations with Sindh’, Karachi 1976. Durate had collected Cutch Agency records as per decision of Government of Sindh. These three volumes of records are availabe in the University of Sindh. His book analyses these sources in details.

[79] Kala, Thirani, ‘British Political Missions to Sindh’, New Delhi, 1974. Incidentally C.L. Mari Walla’s, ‘British Policy towards Sindh’, was also printed just at the time of independence in 1947.

[80] David, Gillard. ‘The Struggle for Asia’, London, 1977. Durpee Louis, ‘Afghanistan. Princeton, 1980, Carries the same view.

[81] Khan, Dr. Munawar, ‘Anglo Afghan Relations 1798-1878’, Peshawar, 1963.

[82] Pakistan Quarterly, Vol, IX, No. 2, pp. 28, 34-64.

[83] Naizindagi, Feb, March, August and December 1954, February and April 1955.

[84] Sayed Hassamuddin Rashdi, Mehran,Vol-VII, part- 278-290,1956.

[85] Lambrick H.T., ‘Charles Napier and Sindh’ Oxford, 1952, and John Jacob of Jaccobabad, Oxford, 1959.

[86] Hamida, Khuhro, ‘Making of Modern Sindh’, Karachi, 1978.

[87] G. M. Sayed,’Sindh-ji-Bombay Khan Alhadgi’, (Sindhi).1969.

[88] Chana Saheb Dino, ‘Separation of Sindh’, Ph.D thesis submitted to Sindh University.,1983.

[89] Hamida Khuhro, ‘Documents on Separation of Sindh.

[90] G. M. Sayed., Sindhi Adabi Board 196.

[91] Rashdi Ali Muhammad. Three volume Sindhi Adabi Board 1966, 1981 and 1983.

[92] Nizamani Karim Bakash, Two volumes. Hyderabad 1981 and 1985

[93] Rashdi Hassamuddin, Sindhi Adabi Board 1977

[94]Aitkin Gazetteer of Sindh, first printed to in 1907, reproduced by Indus Publishers Karachi,1986.

[95] Sorely H.T., ‘Gazetteer of West Pakistan-Sindh’, Karachi, 1968.

[96] Lambrick H.T. ‘The Terrorists’ Ben Press London 1973.

[97] M. H . Panhwar, ‘Source material on Sindh’, Reports and records, pp. 203-226 report Nos. 30, 2535-2887 and pp. 353-365. Reports Nos. 4400-2622. Total 576 reports. 473Maps of Sindh in India Office Library. Jour, Grass Roots 1981 pp. 39-76. The articles give details of 250 Taluka reports, issued every 10th year up to 1932 A.D., with a Taluka map.

[98] Only a few for samples are:

a) Dorthy Balck, ‘Letters of an Indian Judge to an English Women’, London, 1977.

b) Allen, Charles, ’Plain tales from the Raj’ London, 1975.

c) Edwardes Michael, ‘Raj’ London 1976.

d) Allen, Charles, ‘Raj Scrap book of British India’ 1877-1977 London, 1977.

e) ‘Wavell, Scholar Soldier, New York 1966.

f) Thomson Edward, ‘making of indian Prince, London, 1976.

g) Coen, Terence Creagh, Theindian political Service, London, 1977.

h) Mason Philip, ‘A matter of honour, an account of Indian army’, London, 1974.

i) Mollo Boris, ‘The Indian Army’ Poole Darset, 1981.

j) ‘Hough, ‘Mountbatten-Hero of our times’, Londo, 1980.

k) A Large number of biographies, specially of British Viceroys and Governor Generals.

l) Mason Phillip, ‘Men who Ruled India, London 1956.

Source BOOK: SINDHOLOGICAL STUDIES, SUMMER 1986. PAGE:15 -40

The work on this subject was initiated by Dr. Daudpotta in the Persian texts of Chach Namah and Masumi in 1938 and 1940 as already mentioned. These sources were used by Syed Abu Zafar Nadvi to write history of Sindh. It was the first attempt to write history of the Arab governors of Sindh and with analysis of events. The author has done many blunders and distortions and his historical maps are totally in-accurate and un-intelligible[32]. Memon Abdul Majeed has probably used this as the only source for his Sindh and Multan’s Arab governors and has repeated the same chronological mistakes,[33], but it formed definite information for Sindhi scholars as Nadvi’s book was not readily available. Dr. Mumtaz Pathan is the first scholar, who used all scattered material on Arab rule of Sindh. His work so for is the best document on this subject[34]. Dr. N.A. Balouch in his various articles as well as notes on Masummi has referred to Arab governors’ rule of Sindh, but this material is scattered and required re-compilation[35]. R.C. Mujamdar has given references to many new Indian sources on his successors. This new information collected from inscriptions and some contemporary Sanskrit and Gujarati works, has merit of its own[36]. There is also some material in the Archaeological Survey of India’s reports, Bombay Gazetteers/Annals and Histories of Gujarat and finally writings of Arab travellers and merchants.

The present writer made use of all available material, had Arab.

Sources re-verified with the original texts and put all the events in a chronological order[37]. In view of this new material, is possible to re-write this chapter of Sindh’s history.

Archaeological Department of Pakistan has carried out excavation at Banbhore and Brahmanabad-Mansura site. On the first site final report has been issued, work on second site is in progress[38], although in 1979 the dept. issued an official statement that Brahmanabad / Mansura is same site.

Habari Rule of Sindh (854-1011 A.D.)

Dr. Daudpotta had worked out chronological rule of Habaris in notes on Masumi in 1938. This material was utilized by Nadvi to write history of Habaris[39], but the latter work is far from satisfactory and same is case of Memon Abdul Majeed[40]. Dr. Mumtaz Pathan’s Arab kingdom of Mansura is upto date work on the subject. Habaris with the active help of local tribes ruled successfully for 171 years and had maintained good relations with Gujarat, Pratiharas (of Rajasthan, Uttar Pardesh, Bihar and Northern Madhya Pardesh), Rashkuttas of Maharshtra and Hyderabad (Dn). They managed to have good relations with Hindu Shahi rulers of the Punjab; Sammas of Multan and Hindu Sammas and Chawra rulers of Cutch. The political and economic conditions of the period for other areas of Sub-continent are also well known. Present writer was able to locate the courses of the river Indus in the 9th century and from it worked out possible areas under cultivation, as well as the population[41]. A large number of travellers, geographers and merchants, mostly of Persian origin (but popularly called Arab geographers) visited Sindh as well as the Sub-continent and wrote accounts specially pertaining to local produce industry, exportable commodities and etc. These accounts await a full analysis by historical economists. The present writer has covered their chronology in 24 pages and has the guidance of future writers[42].

Soomra Dynasty (1011-1351)

As already mentioned, the sources of original information on Soomra dynasty was Tarikh-i-Bahadur Shahi, which is now lost. This work was used by Firshta, Abul Fazal, Khan-e-Khana, Nizamuddin, Masumi and many other Persian historians of late 16th and early 17th century to write Samma-Soomra history. The Archaeological department of Pakistan had undertaken a survey of Soomra-Samma ruined towns and settlement in Sindh at my request in sixties and large numbers of sites have been located[43], but no explorations have been done. Dr. N. A. Balouch had made serious efforts to build Soomra history from the folk-lore, was written in 15th and 16th centuries and is not a sober history. Besides, Marvi, Laila and Mumal etc. are fictional beings having no real existence. Certain incidents are however too well known and present writer used this material to reconstruct Soomra history:-

A few notes worthy points are:

i. Soomras were Ismailis, was already known, but Abbas H. Hamadani has collected all possible information[44].

ii. Upto 1714 A.D., Soomras practiced lot of Hindu customs[45].

iii. Daulat-i-Alviya a history of Soomras is a forged and unreliable source on Soomras.

iv. That Mahmud of Gaznavi sacked Mansura in 1026 A.D. was already known from works under-taken by Nazim and Habib. Dr. Mumtaz has used same sources to prove this point, but department of archaeology’s statement in “Dawan” should be considered as the last word that Mahmud sacked and burnt Mansura.

v. Mahmud’s army being looted by Jatts of northern Sindh and his avenging on them in 1027-28 is no longer being doubted. Earlier version that Jatts belonged to northern Punjab is no longer valid.

vi. That Sindh remained part of Gaznavid Empire upto 1281 A.D., is disproved. Sindh became independent soon after Mahmud’s death in 1030 A.D.

vii. A 16th century history of Soomras called Muntakhab-ul-Tawarikh by Muhammad Yousif belonging to Maulana Qasimi was reprinted in his foot notes on Tuhfatul-Kiram by Hassamuddin, is a new source and has been helpful in writing Soomra genealogy and adding to our knowledge of Soomra period.

viii. Ismaili sources and biographers of their preachers have also added to our knowledge of Soomra period.

ix. Historians of Gujarat and Rajasthan have also given some information on relations of those States with Sindh, but this information is not fully explored[46].

x. The Persian Historians of Delhi and Mongols, too have given some references to Sindh. These have been tapped to connect a chain of incidents. Such historians are: Tabqat-i-Nasiri, Mubarak-Shahi, Mirat-i-Sikandri, Mirat-i-Ahmedi, Zainul-Akbar, Ibn Asir, Tarikh-i-Utbi, Diwan-i-Farrukhi, Tarikh-i-Behaqi, Al-Abad Saghani’s Taj ul-Masasir (Arabic), Ain-i-Haqiqat namah, Jahan-gusha-i-Juwaini, Rehala of Ibn Battuta, tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi of Barani, Tughlaq name of Amir Khusru, Jami-ul-Tawarikh of Hamadani, and Masalikul absar of Abu-Safa-Sirajuddin Umar.

xi. Jalaluddin Khawarizm Shah after having been defeated by Chengiz Khan was chased by him right upto Attack. The former came to Sindh, sacked Sehwan and burnt Debal, Pari Nagar and some towns in Kathiawar to collect wealth, to re-conquer the lost territories. Chanesar was ruler then.

xii. Ibn Battuta visited Sindh in 1333 A.D., and saw Samma’s rebellion against Delhi government.

xiii. Mohammad Bin Tughlaq took an expedition against Soomras but probably was poisoned and died at Sondha. The imperial troops were chased and looted by Soomras.

The present writer has collected all above material and has reconstructed a history of Soomra over 104 pages[47] discarding folk-lore altogether.

It is possible to collect material on the same lines especially from areas around Sindh to add to our knowledge of Soomras of Sindh. Archaeological explorations can throw light on arts, crafts, economics and day to day life of this period.

Samma Dynasty (1351 – 1224 A.D.)

The situation on Samma period is exactly the same as Soomra Period. Its original source being Tarikh-i-Bahadur Shahi, now lost, from which same histories were copied as mentioned in first paragraph of (v) above. The material being scanty the present writer has made efforts to co-relate various incidents chronologically, to make a continuous chain of events with encouraging results. Luckily for us there are some outside sources of information, for example.

i. Battuta’s visit to Sindh in 1333 A.D. and seeing Sammas under Unar, rebellion[48].

ii. Mohammad Bin Tughlaq’s expedition on Sindh in 1351 A.D. and death at Sondha is better known from various sources including Mahdi-Hussain Agha[49] and 14th century historian Ziauddin Barani’s Tarikh-i-feroz Shahi. That he was poisoned to death is elaborated by Mahdi Hassan. His temporary burial at Sehwan for the first time discovered by Professor Muhammad Shafi in 1935[50], was brought to the notice of Sindhis by Dr. Daudpotta’s Masumi in 1938. It has been reproduced by many scholars in various jouranls including Alwahid’s “Sindh Azad Number” in 1936.

iii. The Samma’s overthrew Soomras soon after 1335 A.D. and the last Soomra ruler took shelter with Feroz Shah’s governor of Gujarat is known from “Insha-e-Mahru, a collection of 101 letters of Mahru, the governor of Multan and a master mind of his age[51]. Mahru managed that Feroze-Shah may take expedition against Sindh to restore Hamir Dodo. Preparation started in 1364 A.D., and in 1365 having lost the battle with Sammas and 5000 boats destroyed by Cutchi seamen, the Sultan left for Gujarat via Cutch, where Cutchi guerillas attacked and destroyed his whole army[52]. With new re-inforcements he marched on Sindh, via the desert in September 1366 A.D. and lost battle after one year in October 1367 A.D. but with new inforcements from Delhi and putting Makhdoom Jehania of Uch as mediator, he made Banbhiniyo to surrender[53]. That this Makhdoom came to the rescue of Feroz Shah three or four times bringing compromise between Delhi and Sammas to the advantage of Sultan, is brilliantly described by Dr. Riazul-Islam[54]. This work of Riazul-Islam covers Samma period upto 1388 A.D.

iv. On Ferozshah’s death, Delhi Sultanate disintegrated and Sammas became independent. The chronology of Sammas first worked out by Hodiwala[55] in 1939 was corrected by Dr. Balouch[56]. The present writer re-verified the original sources and has revised the above two version[57]. Hassamuddin in Tarkhan-Nama and Tuhfatul Kiram has used Dr. Balouch’s chronology with acknowledgements[58].

v. Information on Sammas from 1386 – 1508 is very scanty and scattered sources like Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi by Afif, Frishta, Masumi, Mubarak-Shahi, Tabqat-i-Akbari, Tahiri, Mazahar Shah Jehani, Tarkhan Namah, History and Culture of Indian People. Vol. IV, Tarikh-i-Shahi, Maraat-i-Sikandri, Maraat-i-Ahmedi, Tuhfatul-Kiram, Todd’s Rajasthan, Ain-i-Akbari, Maathir-i-Rahimi and Hadiqatual-Aulia have all been tapped by the present writer to cover this period in 28 pages[59]. Three other sources little known in Sindh on this period are Zafarul Walih[60] Bahawalpur District Gazetteer[61], and Subuh-al-Asga[62].

vi. On Sindh-Gujarat and Sindh-cutch relations, Miraat-i-Ahmedi[63], Maraat-i-Sikandri[64] and William’s Black Hills throw new light, which shows that due to interference of Jam Feroz into a dispute between two ruling cousins of cutch, the aggrieved party Rao Khenghar helped Jam Salahuddin twice, first time to over throw Feroz and next time to fight Shah Hassan and Shah Beg, who had restored Feroz. Later he helped Feroz to fight Arghoons. Cambridge History of India[65] and Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency[66] give information about Jam of Nizamuddin’s period.

Nizamuddin’s period.

vii. On Samma’s down-fall (1508-1524), besides Williams and other sources are mentioned in (IV) and (V) above, Tuzuk Babri, or Babur Nama in another important document.

viii. Chronology of the period from 1508 to 1524 A.D. as given by Masumi is defective. This has been corrected by Dr. M.H. Siddiqi. He also has describes Balouch migration to Sindh during the same period in one appendix. Dr. Siddiqi also describes Mehdi Jaunpur’s mission to Sindh in 1501-1503 A.D. The failure of this mission and sinking of his boats by Hyder Shah of Sann at the instruction of Makhdoom Bilawal is described by G.M. Sayed.

Pakistan’s Archaeological Dept. has done virtually no work on this period, except a single season’s survey mentioned in Ref. (44). Ghafur wrote on calligraphers of Thatta, a work of minor importance and two monographs on Thatta by Shamasuddin and Siddiqi Idris, were published by the Deptt. Of Archaeology. The department helped Hassamuddin with a large number of photographs for his Makli Nama and Tuhfatul-Kiram. Dr. Dani’s Thatta, is based on Hassamuddin’s work. Hassamuddin used Khan Khudadad Khan Persian manuscript ‘Biaz’ for Makli Nama. Baiz[67] has sketches of graves with sketches of inscriptions and also inscriptions re-written in plain Persian alphabet for convenience. The post-independence archaeological work on the Samma period of Sindh therefore may be considered as almost nil and we have to revert back to Cousens ‘Antiquities of Sindh’, actually written in 1908-09, but printed in 1925.

Arghoon (1524-1554) Tarkhans 1554-1591 and Mughals (1587-1736 A.D.)

Information on this period before the independence was scanty. All credit for work on this period goes to Sindhi Adabi Board, who published a large number of Persian history tests, poetical works giving references on Sindh and a number of articles in Jour. Mehran. Of the prominent scholars who did this work the out-standing were Hassamuddin Rashdi and Dr. N.A Balouch. The former has specialized in the Mughal period of History of Sindh and more than 90% of his work on Sindh was on this period i.e. 1500-1750 A.D[68]

In various books Hassamuddin has given elaborate footnotes from contemporary historians mostly of the Mughal court. His Urdu and Persian works published by other organizations do not pertain to Sindh, but all the same belong mostly to the Mughal period. He has almost exhausted all known material on Sindh in Persian, written on the period 1500-1700 A.D., as most of material available pertains to Kalhora period and he had not specialized in it.

Dr. N.A. Balouch, essentially a scholar of Sindhi language and Sindhi folk lore, has been writing on arts and crafts of Sindh and some biographical Sketches. He edited two Persian historical works for Sindhi Adabi Board and wrote exhaustive notes on Chach-Namah and Masumi. He also wrote on some archaeological sites, but limiting himself to history of the place rather than archaeology[69]. These two scholars have remained on the fore-front in research on history of Sindh. Although Hassamuddin exhausted almost all Persian sources of this period, he did not touch English and European sources. Plentiful work has been done in English on Mughal administration, economic conditions foreign trade, foreign relations European travellers’ accounts and provincial administration of the Mughals, but as the specialist on Persian sources of Sindh’s History, he has eliminated them altogether, except occasional references to Haig and a few others. In his notes on the Persian texts most of which are in Sindhi, he has given quotations from Persian texts but these quotations have not been translated. Makli Nama which has 90 pages of Persian text and more than 700 pages of the notes in Sindhi is a monumental work. The Persian text in un-translated and is still in original form. Sindhi Adabi Board published Mazhar-Shah-Jehani, translated into Sindhi and book soon went out of stock. Unless this vast material on this period of Sindh’s past is translated, the young historians ignorant of Persian can not make any use of it. For the analysis of Mughal rule in Sindh, European sources also have to be re-examined[70].

Dr. Balouch’s two Persian texts also belong to this period of Sindh’s history and thus we are fully equipped to write an authentic history of Arghoon, Tarkhans and Mughal governors of Sindh.

On the examination of histories of the period specially Mazhar Shah Jehani and Beglar Nama, British factory records (1635-1662) and European travelers’ accounts, one finds that this was the period of great turmoil. Sindhis from the Urban areas, specially Ulama and business men had migrated to Cutch, Gujarat, Burhanpur and Arabia. The Arghoon had deliberately forced the population to quit the Urban areas to create place for their own people, who under pressures of Babur had to leave their own settlements in Central Asia and Afghanistan. During the Tarkhan period Sindhis started a kind of civil war, which continued through, up to Kalhora take over. Present writer has published detailed article on this civil war[71]. This could also be looked from the other angle of ruling class of the period and every action may be justified on the basis of local’s rebellion against the government. Dr. Zahid Ahmed Khan has approached the Subject from that angle[72].

These two views need critical examination by a third party, but the fact was that there was no peace during the period and the economy had dwindled, marking it easy for Kalhoras take over in the very life time of Aurangzeb.

Kalhoras dynasty (1700-1783)

As stated earlier there was plenty of scattered material on Kalhoras period mostly in the form of manuscripts, but no history based on even on fragmentary material exited. Qani’s Tuhfatul Kiram had only a few pages on Kalhoras. Sindhi Adabi Board assigned this job to Ghullam Rasool Mahar and published ‘A history of Kalhoras’ in 2 volumes. He used a very large number of Persian and English sources to construct the history of Kalhoras. The author has done some justice to the subject, specially looking to the vast material thus collected in historical sequence[73].

Dr. Riazul-Islam has now published two volumes of correspondence on Mughal and Nadir Shah’s court. This throws new light on the subject and needs a new thinking, McMurdo Waiqia-i-Sindh or History of Kalhoras has also gone unnoticed by Mahar. Dr. Balock N.A’s. ‘The last of Kalhora Princes of Sindh[74], was not known to Mahar. Mahar also has failed to analyse economic circumstances leading to the disintegration of he Mughal Empire, which led to Kalhoras quick rise to power. Economic conditions have not been properly looked into. The Sufi movements, which rose in 16th and 17th century to counter, balance the ritualistic religious group, have been over-looked. It is 28 years, since the book was first published and there is a need for a new version of history of Kalhoras. The sanads and letters of Kalhoras available in manuscript form are another large source of material on this period.

In the field of archaeology, no work has been done on this period. The leading Baouch Sardars, who came with Mian Nasir, are all buried near Gharhi at Mian Nasir’s grave yard. Their descendents too were being buried there, until the first half of this century. This major grave yard needs an archaeologist eye and reconstruction of the history.

Talpur rule of Sindh 1783-1843

Sindhi Adabi Board has published Azim’s ‘Fateh Nama’ a poetical work on the Civil War leading to the down-fall of Kalhoras and rise of Talpurs. The study of economic conditions of Sindh during the Kalhoras period shows that in 1758 A.D., the area under cultivation in Sindh was 22 lakh acres and population 30 lakhs. During this year there was a major change in the course of the river Indus, which abandoned its course near Hala and taking the present course west of Hyderabad. Earlier it was flowing from Hala to Odero Lal, Shaikh Bhirkio, Tando Muhammad Khan, Matli and Badin to Koree Creek. This major change put 10 lakh acres out of cultivation. People were up-rooted. Building of new canals would take many years patience. Such changes invariably have brought changes of dynasties in the past. The resulting strife due to this change was in form of civil-war between Noor Muhammad Kalhoras sons, where Ghullam Shah with support of Balouch Sardars was installed as ruler. Subsequent events were simply strife to hold the cultivable land. It finally ended in change of the government from Kalhoras to Talpurs in 1738 A.D.

The new rulers soon got involved into an international political triangle. Since 1783 Russia has started expanding towards India and British from Calcutta had started a move west-ward. By 1799 it was clear that the two powers were to have a clash. The British planned to reach the Indus at the earliest and later on planned to meet Russians at Oxus or beyond. Sindh and Punjab had to be subdued. The major part of Talpur history therefore is their relations with the British. Many writers like Advani, Mariwala and Mirchandani wrote on British designs on Sindh. This prepared a way for collection of source material on Sindh. Khera Published a small book on the subject from Lahore in 1946, but detailed work was yet to be done. The first work after independence was of Lambrick’s[75].

In this scholarly work the learned author unbiasly has described Talpur-British relations from 1799-1843, leading to conquest of Sindh and details of the Sindh battles: Huttenback[76] was next author to elaborate this work further. He was able to use India office records in London in more details than Lambrick. Truly as the title suggests, it was dissection of Imperial designs. He correctly identified relations in 5 phases[77].

Dr. Duarte who had also written on the same subject in early fifties, tried desperately to have his book published but its publication was blocked on the basis of being biased and favourable to the British. The book was not published until at orders of the late Mr. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1976[78]. Meantime Kala Therani using mostly records from Archives of India, published yet another book[79].

Two other books by Gillard[80] and Khan[81]gives yet another version of the necessity of British conquest of Sindh and major factors involve. In terms of material, the studies done are concrete and there seems nothing new to be added to this subject unless new records come to light. The history of Talpur period is still to be written. Scattered articles, some of scholarly merit like Duarte’s ‘Court of Talpurs[82], Karachi Mirza Gul Hassan Beg’s literary persuits of Talpurs[83], Hassamuddin’s Seals of Talpurs’[84], and Mayer L.A’s Islamic armours and their work, Geneva (1963), depicts Talpur swords. These are but a few of many standard articles. Talpur correspondence, letters, Sanads and etc. in manuscript form exist with various families, individuals and institutes.

Many Talpur have family records. The ruling families museum is another collection of arts and crafts of the period. History of alienation and history of Jagirs form vast material on the period and so are early British records bluebooks, reports and travellers documents.

All this scattered material could be collected, translated and published to form source material for study of this period.

British Period. (1843-1947 A.D.)

This is so recent a period and there is so much material available that there should have been a maximum number of publications on it. Unfortunately this is not the case. Since independence, only first 16 years of British rule are covered to some extent by two books of Lambrick ‘Charles Napier and Sindh’ and ‘John Jacob of Jaccobabad[85], and Dr. Hamida Khuhro’s[86] Making of Modern Sindh’, which is dissertation on Sir Bartle Frere’s administration of Sindh from 1251-1859. Other works of some merit are on the separation of Sindh from Bombay presidency by G.M. Sayed[87] and Ph.D. Thesis of Saheb Dino Chana[88]. To these may also be aded Hamida Khhro’s collection of documents on the same subject in two volumes[89].

The rest of period is a large vacuum. A number of books written by British and Western writers discuss this period of Sindh’s history in different context or bio-graphies but these may be considered only the source material. In the same way four bio-graphics by G. M . Sayed[90].

All Muhammad Rashdi[91], Kairm Baksh Nazamani[92] and Hassamuddin Rashdi[93] are only source material for use of future historians. The Gazetteers were used as ready beckoners. One such Gazetteer by Sorley was published by the Government of West Pakistan, in 1969. It is history of the British administration of Sindh from 1905 to 1947[94], The West Pakistan editors of this Gazetteer took liberty of changing the text or expurgating portions of it. Thus we no longer have the benefit of knowing some important observations of author on working of provincial administration of Sindh since 1935 and also his own observations on the circumstances leading to formation of Pakistan.

In any case the book is indispensable for the histories of the British period from 1805-1947. Aitkin’s Gazetteer of Sindh, first printed in 1907, and has recently been reproduced by Indus Publishers, Karachi, with an introduction by Mazhar Yusuf, who is also Honey. Editor of the Sindhological Studies, from the very inception of the Journal[95].

During the period there were a number of political, social, and religious movements, for example.-

1. Hur movements, of 1890-1900, 1910-15, 1941-47.

2. Khilafat Movement, 1917-1924.

3. Separation of Sindh movement 1913-1933.

4. Muslim League and Pakistan Movement. 1938-1947.

No complete history of above movements has yet been written.

Lambricks,[96] books on Hurs is information as the British officials saw and thought of the movement.

The British period records are well preserved in the India office Library in form of numerous reports. One important series of the reports was “Annual administrative report of the Bombay Presidency from 1861-1933 and thence after there were annual administrative reports of each department of province of Sindh.

Another series of the reports was “Revised Survey and settlement reports of each Taluka of the province” issued every 10th year since 1871 to 1932. The report gave crops cropped areas, irrigated areas, population of each Taluka. The census reports besides statistics give important information on language, ethnic groups, castes and tribes. All these reports are rare in Sindh but are preserved in the India Office Library.

In 1982, the Irrigation Department of Sindh invited scholars and engineers to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Sukkur Barrage and to write on the history and impact of Sukkur Barrage. These papers are being printed in two volumes by the department and they cover the complete history of irrigation during the British period.

The present writer has listed the names of reports of the British period, mostly available with him, in ‘Source Material on Sindh[97] and maps of Sindh in the India Official Library, British Museum, Royal Geographical Society and Archives of India.

Debates of Bombay Legislature 1923-1935, Sindh Assembly 1937-1947, is another source and so are the Round Table Conference proceedings. In fact the detailed history of developments in each government department and institute needs to be written. The above information is given as a guide line for scholars interested in writing the history of British Rule in Sindh.

British developed a new type of architecture in Sindh for their offices, schools, public utilities etc. Under them the private owners for their buildings in the towns also adopted a new type of architecture. Some of these buildings are monuments worth preserving but they are being pulled down by the owners as well as governmental agencies. This amounts to destruction of our history as much as destruction of our archaeological sites. No engineer has come forward to write on British architecture in Sindh, its evolution, maturity and special features. This should form top priority for our historians. The daily ‘Evening Star’ has started a crusade to save Karachi’s huildings from destruction. 5000 private and government buildings will form part of this project. The work has not been extended to Sindh, where even in the rural areas Wadera’s Autaq was a copy of either a school or an office building.

It is interesting to note that all government buildings before 1880 A.D., used wood beams and raftars. After 1880 A.D., they switched over to girders, T-irons and brick tiles or wooden planks. Reinforced concrete was not introduced until 1915, but its use on a wide scale came after 1930. It did not reach rural Sindh until after independence.